Zenith Energy Before and After—A Brief History

A Toxic Legacy

Zenith Energy’s Portland Terminal is a fossil fuel transloading facility—accepting fuel products from one mode of transportation and passing them along to another. Most, if not all, of the product Zenith handles is destined for other places in the U.S.—it’s not used here in Oregon. The site has operated as a petroleum products storage terminal since 1947. The 39-acre site has 84 tanks with a total storage capacity of 1,518,200 barrels. Around 2013, Zenith’s predecessor, Arc Logistics, started using the facility to refine crude oil. Zenith took over in December 2017, and within one month was importing tar sands and crude oil to the Portland Terminal on mile-long trains from Canada and North Dakota.

Zenith is located in NW Portland (5501 NW Front Ave) in what is now known as the Critical Energy Infrastructure Hub—a strategically placed sacrifice zone that stores millions of gallons of fuel, chemicals, and other toxic substances—located on the banks of the Willamette River. Unfortunately, this six-mile stretch of aging tank farms—reaching from the southern edge of Sauvie Island to the Fremont Bridge— is smack dab in the middle of a liquefaction zone. Liquefaction occurs in saturated soils, when the space between individual particles of soil is filled with water. This means, if there is an earthquake, the ground beneath the area would turn to the consistency of cake batter—an undesirable foundation for the millions of gallons of dangerous substances stored there.

A Racist History

Of course, it didn’t always look like this. Since time immemorial, Native Americans lived on and cared for this land. Once covered with cedar, white ash, willow, and fir trees, at the turn of the last century, Guild’s Lake was a shallow, marshy area fed by Balch creek and groundwater, rising and falling with seasonal changes, and eventually feeding into the Willamette River. Sitting just below what is now known as Forest Park, the area was abundant with fish, wildlife, and easy access to the river—a feature that would contribute to its later development into the industrial sacrifice zone we see today.

The history of development on this land is a shared history of displacement and disproportionate burdens on BIPOC and low-income communities: Indigenous people who inhabited the land since time immemorial, Chinese immigrants who farmed small plots along the edge of the lake in the 1880s, Black families who moved to the area during WWII, and surrounding communities disproportionately affected by pollution from industries in this area today.

Guild’s Lake was named after Peter Guild, one of the first 19th-century settlers in the area, who acquired the nearly 600 acres around the lake through a donation land claim. The Donation Land Claim Act was a privilege allowed to white men or partial Native Americans (mixed with white) who had arrived in Oregon before 1850 to work on a piece of land for four years and then legally claim the land as their own.

After Guild died in 1870, landowners soon began modifying the area to accommodate industrial uses. In the 1880s, Northern Pacific Railway built the Guild’s Lake Rail Yard—an important feature for train switching operations. Soon after, Northern Pacific built an embankment for a rail connection between Portland and Seattle—cutting off the lake’s outlet to the Willamette River.

Channel-deepening in the Willamette River began in the 1890s, giving Portland status as a deep-water port. By the end of the century, real estate speculators owned much of the land in and around the lake, and operations of several sawmills, shipping docks, and a garbage incinerator had also begun.

A Trail of Exploitation

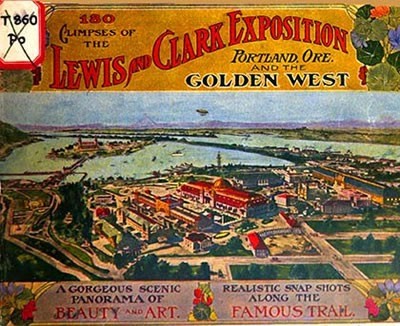

In 1902, the area was chosen as the site of the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition—often informally considered a World’s Fair. Two years of landscaping transformed the area into an impressive site of massive buildings, winding paths, and a sparkling lake complete with a 2000 foot-long “Bride of Nations.” The exposition was expected to boost the economy of the region and it attracted roughly 1.6 million visitors in its four-month run.

Portland was an important Pacific shipping port, so planners and supporters of the exposition strongly emphasized how much Oregon had to gain by reaching out to new markets. Promoting the West as a hub of economic activity, the exposition was designed to justify the traditions of colonialism and continuing the move westward—the arch over the entrance gate stating, "Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way"—laying the groundwork for expansion into Asia.

Highly racist in content, “live displays” of Native American, Filipino, and Japanese people were featured throughout the exhibition, offering visitors opportunities to “learn about” the westward expansion and the groups and cultures that lived on the Pacific Coast.

Touted as a successful effort highlighting the natural richness of the region and its relative nearness to Asia, the visual transformation resulting from the exposition was short lived. The next year, the area was leveled for construction and in 1906, the Oregonian reported “the bare mudflat” had lost its appeal.

The Making of a Sacrifice Zone

In the years following, the riverbed was pumped up and dumped into the lake. During the same time, massive amounts of dirt were being removed to support development in the hills of Portland. The area was made ideal for industrial land: flat, open, easy access to rail lines and a seaport. Conversion to industrial development happened quickly. By the 1930s, there was no trace the lake had ever been there.

WWII brought a boon to the shipyards and following the war, large-scale industrial development continued. Conversion of this once riparian wetland has led us to the dangerous ticking time bomb we now face—millions of gallons of flammable liquids stored on top of a known liquefaction zone.

Hope for the Future

Today, the lake is unrecognizable—lying beneath acres of fill dirt on the river side of Highway 30, just as it cuts away from Interstate 405. The area Zenith is currently looking to develop has not been used since World War II. This is the perfect opportunity for Portland to walk the talk and make sure that this land is used in ways that will not harm surrounding communities.

Zenith too will someday become part of the history of this place—as will all of you and others who have fought so hard to protect it. It is up to us to determine what the impact of that history will be. This is a place worth protecting. With a better understanding and vision for the future, together, we can do it!

Check out these resources to learn more:

- https://braidedrivercampaignpdx.org

- https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/guild_s_lake/#.YIG2OC2cY0p

- https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/lewis_clark_exposition/#.YIHK8y2cb_Q

- https://www.oregonhistoryproject.org/articles/historical-records/guild39s-lake-1904/#.YIG2xC2cY0o

- http://www.offbeatoregon.com/1210d-guilds-lake-portlands-water-wonderland.html

- https://www.ohs.org/blog/meet-you-on-the-trail.cfm

- https://www.ohs.org/research-and-library/oregon-historical-quarterly/upload/Blee-Completing-Lewis-and-Clark.pdf

- https://www.portlandmercury.com/feature/2019/11/21/27511074/on-shaky-ground

Stunning new fossil fuel proposals threaten the Columbia. The good news? We are fighting and winning!