Intimate discussion on the history of modern conservation, from the early battles to save “fuzzy mammals” to the current fight to shift global priorities from extinction to abundance.

Conservation for the Curious with Michelle Nijhuis

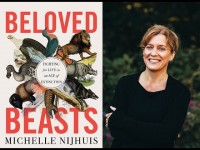

Michelle Nijhuis is a journalist and award-winning author of “Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction.” With stunning vignettes and interwoven narratives, “Beloved Beasts” explores the history of modern conservation, from Linnaeus to current community conservation efforts in Namibia. Our interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What inspired you to write this book at this time?

I have a background in biology, and when I became a journalist I noticed that even professional conservationists and people who care deeply about conservation didn’t have a very strong understanding of the history of conservation as a movement. This is understandable because they’re focused on the emergencies in front of them. But I think it’s crucial to understand what activists before us have done right—and what they’ve done wrong and overlooked.

The book goes beyond a discrete history of modern conservation; each chapter builds on the previous. Why did you take this approach?

One of the most interesting parts of my research was learning about all the connections among well-known conservationists. They exchanged letters, they argued, and sometimes they clashed in quite dramatic ways over their ideas and strategies. We tend to think of these people as isolated icons, but they worked together—even across generations—and they helped build a movement that’s evolved over time.

The modern history of conservation is, until recently, white and affluent. Racism and colonialism were prevalent, and remain ongoing issues today. Why were conservation and colonialism so intertwined?

My book is a history of the “modern conservation movement,” which I define as the movement that began in Europe and North America in the late 1800s— when many people in those societies first understood that humans could drive species globally extinct. It’s important for me to define my terms because modern conservation has overlooked and ignored a lot of more local, traditional conservation practices that have existed since the beginning of human history.

The modern conservation movement did begin as an elite movement. The people with power in Europe and North America had a first-hand look at what industrialized societies were doing to other species. They had the resources and the education that allowed them to understand that this was happening on a global scale. They had privileges that allowed them to voice their opinion without fear of retribution. To their credit, I think the leaders of the early modern conservation movement had the foresight to connect people with species that they might never encounter in life, but whose fates their actions nevertheless affected. However, the elite, white, predominantly male roots of the movement have meant that modern conservation has often defaulted to topdown, centralized authority as a strategy. The movement also tended to follow colonial paths and work with colonial governments when it did leave North America and Europe, more or less imposing conservation rules and regulations on colonized peoples.

It’s taken the modern conservation movement a long time to begin working more closely with existing, local conservation practices and realize that they are essential to what we might call the “conservation ecosystem.” Conservation can’t simply rely on boundaries and prohibitive laws if we want conservation to operate both ethically and on a global scale.

Any advice you’d give to budding conservationists?

I think community-led conservation is one of the most exciting directions that conservation is taking right now. The modern conservation movement is realizing that one of the most ethical and effective ways to get conservation done is to support the people whose communities have been practicing conservation for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. These efforts are working with species that are often not in crisis, that are still abundant in many ways, and that’s almost a joyful kind of work to be doing because you’re working not just to prevent extinction but to restore relationships. I would encourage young conservationists, especially those who are worried about conservation being a depressing field, to check out the exciting, innovative work being done in that realm.

Do you have a favorite species?

I’ve been a fan of frogs ever since I was a little kid. I’m not a fan of any particular species of frog, but I love frogs and amphibians in general. They get to be two animals, and live in two habitats—how cool is that? “Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction” is available online and at your local bookstore. If you’d like to watch my full interview with Michelle, click here.

Oil-by-rail heating up; dive in at secret beaches; illegal pollution from dams; and Love Your Columbia educational series.