The Rise and Fall of Lower Snake River Dams

A Brief Timeline

Listen or read now

Since time immemorial Indigenous people and Tribes live and fish in the region now known as the Lower Snake River.

Four Columbia River Tribes sign treaties with the United States reserving their rights to take salmon at “all usual and accustomed places,” including the Lower Snake River.

Washington Dept. of Fisheries opposes building four dams on the Lower Snake River because they would “jeopardiz[e] more than one-half of the Columbia River salmon production in exchange for 148 miles of subsidized barge route.”

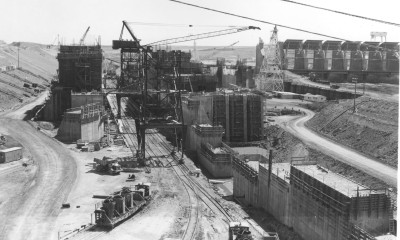

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers constructs four dams on the Lower Snake River, drowning the “usual and accustomed fishing places” protected by Tribal treaties.

Snake River coho salmon go extinct.

Shoshone-Bannock Tribes successfully petition the federal government to list Snake River sockeye salmon under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Spring-and fall-run Snake River Chinook salmon are ESA-listed in 1992.

Nez Perce Tribe begins reintroduction of Snake River coho salmon.

Tribes, states, and fishing and conservation groups, including Columbia Riverkeeper, sue the federal government under the ESA for failing to create a plan (called a Biological Opinion) to protect and recover salmon populations. Judges in the case strike down multiple federal plans as inadequate and order marginal improvements to the dams’ operation to protect fish.

Snake River steelhead are ESA-listed.

Rep. Mike Simpson (R-ID) outlines an ambitious proposal to un-dam the Lower Snake River and re-invest in river communities.

The Biden Administration promises a “durable solution” to restore abundant salmon, and acknowledges that Lower Snake River dam removal is “essential” to that goal.

2023 Hopefully, the Biden Administration will release a comprehensive plan to recover Columbia Basin salmon, honor tribal rights, and replace the services of the Lower Snake River dams.

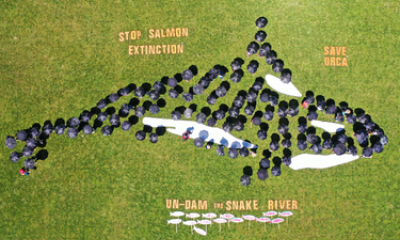

Salmon Unite Us: Join the Fight for Recovery

Want to hear all the stories from Columbia Riverkeeper's Currents Issue 2, 2023 Newsletter?

Tell Northwest leaders and Pres. Biden to remove Snake River dams, prevent salmon extinction, and honor Tribal rights.