By: Audrey Leonard, Staff Attorney

At Columbia Riverkeeper, we look beyond industry promises to determine the real impacts, risks, and benefits of energy projects. The proposed NEXT refinery at Port Westward promises to support Oregon’s climate goals by making “renewable” diesel—but the refinery could emit 1 million tons of greenhouse gas pollution per year and use as much fracked gas as the entire city of Eugene.

Our new report explains why NEXT is unlikely to be able to make large quantities of truly low-carbon fuel. This isn’t just a bad deal for climate—it also has negative financial implications for NEXT.

NEXT would be the second largest renewable diesel refinery in the United States, with a nameplate capacity of 750 million gallons per year.

Understanding what feedstocks NEXT will use is essential to evaluating the refinery’s climate impacts.

“Renewable” diesel is made out of non-petroleum feedstocks and is processed to be chemically the same as regular diesel. However, feedstocks vary in price, availability, and climate impacts.

Common types of feedstocks for renewable diesel include:

- Vegetable oils: soybean oil, canola oil, corn oil

- Animal fats: tallow, lard, fish oil

- Used cooking oil

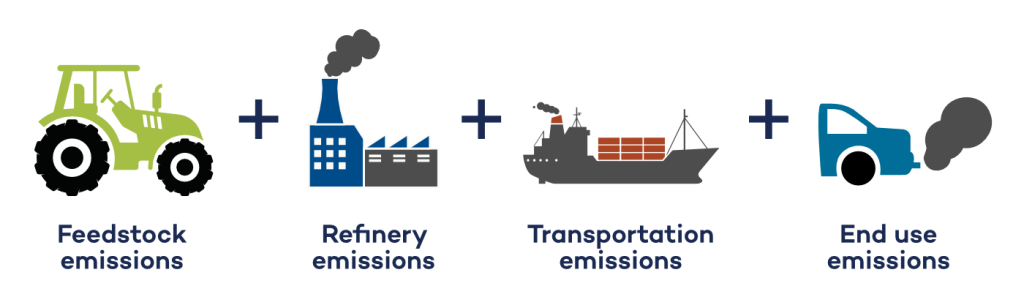

Soybean and canola oil feedstocks have the highest “carbon-intensity” due to energy-intensive production processes which rely heavily on fossil fuels and result in substantial greenhouse gas emissions. Consider the fossil fuels required to run farm equipment for planting, spraying herbicides, and harvesting crops; to power the process of turning soybeans into oil; and to transport processed oils to a refinery.

NEXT is very unlikely to make fuel primarily from low-carbon feedstocks.

Feedstocks that come from waste products, like used cooking oil or waste animal fats, have a lower carbon-intensity because they are byproducts. NEXT has repeatedly mentioned using these kinds of feedstocks, like fish grease. However, our report shows that the amount and availability of these low-carbon, waste feedstocks is limited. Existing renewable diesel refineries are already using nearly all of the available supply, and NEXT has not secured contracts to purchase any of these scarce, low-carbon feedstocks. Accordingly, the report found that it will likely be difficult, or too expensive, for NEXT to use meaningful quantities of the low-carbon feedstocks.

Instead, new “renewable” diesel facilities, including NEXT, will mostly use high-carbon, purpose-grown edible vegetable oils. In 2025, these kinds of high-carbon feedstocks are projected to account for 92 percent of the feedstock mix for new renewable diesel refineries like NEXT’s. Low-carbon feedstocks like used cooking oil and animal fats will make up just 8 percent. Because NEXT has not provided any evidence that it could acquire large amounts of low-carbon feedstocks, it appears likely that these scarce feedstocks would be a small fraction of NEXT’s total feedstock supply.

For NEXT, difficulty obtaining low-carbon feedstocks means dirtier fuel—and financial challenges.

Because NEXT would rely heavily on high-carbon vegetable oils to meet its enormous feedstock needs, NEXT’s fuel would be worse for the climate than NEXT promised. Using high-carbon vegetable oil feedstocks could also negatively impact NEXT’s finances by limiting NEXT’s access to important markets.

California, Oregon, Washington, and the City of Portland have rules encouraging renewable fuel use. These rules and credit-trading programs make low-carbon “renewable” diesel more valuable than high-carbon “renewable” (or conventional) diesel, and these financial incentives are part of the business case for NEXT’s refinery. But because NEXT would have trouble finding low-carbon feedstock, the fuel that NEXT produces could be significantly less valuable than NEXT predicted.

Additionally, new rules would limit NEXT’s profitability in important markets that generate lucrative carbon-offset credits. California (where most renewable diesel is used in the U.S.) recently updated its Low Carbon Fuel Standard to limit eligibility for fuels made from food crops to just 20 percent of a refinery’s annual production. This rule change means that a lot of NEXT’s fuel could be ineligible for valuable credits when sold in California, a blow to NEXT’s profit margin. Similarly, the City of Portland set carbon intensity standards in its Clean Fuel Standard program to exclude diesel made from food crops, limiting NEXT’s ability to access this market as well (although NEXT is working to loosen these standards). Oregon and Washington do not yet have similar restrictions, but tend to follow California’s lead when regulating so-called renewable fuels and the states have agreed to collaborate on climate policy.

Take Action: Port Westward

Tell DEQ and Gov. Kotek to protect the Columbia River and our climate from NEXT’s pollution and greenwashing.